A Pedro Pablo Mutumbajoy lo fumigaron tres veces: las primeras dos, a comienzos de siglo, tenía coca en su finca, pero la última no.

En septiembre de 2013, este campesino de Putumayo –en la frontera sur de Colombia- cuidaba un cultivo agroforestal de árboles nativos como achapos o aceitunos, que él había sembrado con esmero y de cuya madera planeaba vivir más adelante. Esa era –y sigue siendo- su apuesta por un sustento alejado de la coca.

Un mes después de que las avionetas de la Policía Antinarcóticos sobrevolaron su finca, rociando glifosato desde el cielo sobre su bosque productivo, Mutumbajoy fue a la alcaldía de Puerto Guzmán e interpuso una queja. En ella, solicitó al Estado colombiano que evaluara los daños a su cultivo legal. Como evidencia adjuntó las fotos de los daños y pidió que lo compensaran económicamente por la pérdida de 350 incipientes árboles. El perjuicio representaba, según este campesino de 48 años, de voz tenue pero carácter decidido, una sexta parte de los que llevaba nueve meses sembrando.

Cuatro meses después, en febrero de 2014, recibió una respuesta: su reclamo “no procedía” porque la Policía decía no haber encontrado cultivos agrícolas en su predio, pero sí en cambio coca. Ni una palabra sobre su proyecto forestal, que para el Estado no cupo en la descripción de cultivo agrícola. Mutumbajoy apeló, pero la Policía rechazó su recurso por tardío. Un error administrativo y un día feriado contado como hábil bastaron para que le dijeran que estaba fuera de los tiempos legales y que, por lo tanto, no seguiría siendo examinado. No ha sabido nada más de su reclamo hasta hoy.

A 1.072 kilómetros de la finca de Mutumbajoy, otro Pedro Pablo lleva aún más tiempo en un calvario similar. En la zona de ciénagas y humedales que abundan en el tramo medio del río Magdalena, en el norte del país, Pedro Pablo Moreno intentó durante más de cuatro años obtener una respuesta del Estado colombiano por la doble aspersión de su finca –primero en 2003 y luego en 2006- en Simití, en el sur de Bolívar.

Moreno asegura no haber tenido nunca coca, pero los policías antidrogas se empeñaron en lo contrario – aunque nunca le mostraron el acta de la visita en donde la detectaron. Ni siquiera una reunión con la primera dama Lina Moreno, esposa del entonces presidente Álvaro Uribe, ni conversaciones y cartas con varios altos funcionarios del gobierno, lograron que Pedro Pablo obtuviera una respuesta de fondo de la Policía Nacional, más allá de tecnicismos legales.

Los casos de los dos Pedro Pablo ilustran el laberinto kafkiano al que se han enfrentado en las últimas dos décadas cientos de campesinos que han buscado reclamar al Estado que evalúe daños materiales causados por la aspersión aérea, la principal estrategia usada por Colombia –con apoyo político, recursos, equipos e incluso contratistas civiles de Estados Unidos- para frenar los cultivos de coca, aquellos de donde se obtiene el alcaloide usado para producir la cocaína que luego es exportada. Para complicar aún más las cosas (y sus casos), la misma Policía que los fumigó era la juez que decidía si sus reclamos eran válidos.

La falta de respuesta del Estado a los afectados por la aspersión aérea con glifosato que ha dañado sus cultivos lícitos cobra revelancia especial en momentos en que este debate, que marcó la política antidrogas de Colombia durante casi dos décadas, está de nuevo sobre la mesa. El presidente Iván Duque, a siete meses de salir del cargo, insiste en revivir la fumigación con avionetas para eliminar los cocales que existen en el país. Según el último censo anual de la Oficina de Naciones Unidas contra la Droga y el Delito (Unodc), a finales de 2020 había 143 mil hectáreas del cultivo en Colombia.

Para hacerlo, su gobierno deberá demostrar que fumigar la coca no causa impactos en la salud de comunidades aledañas ni al ambiente, de acuerdo a los requisitos que fijó la Corte Constitucional en una sentencia de 2017. Esas reglas de juego más estrictas son el resultado de un debate internacional sobre los posibles efectos negativos del glifosato en la salud humana, que se ha agudizado en años recientes. Sobre todo desde que el Centro Internacional de Investigaciones sobre Cáncer (Iarc) –brazo de investigación de la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS)- lo reclasificó como sustancia probablemente cancerígena en 2015, llevando al gobierno de su antecesor Juan Manuel Santos a suspender preventivamente su uso para fumigar coca.

Aunque la atención pública se ha centrado en las condiciones sobre la salud humana y el ambiente, contar con un sistema robusto de atención a reclamos es otra de las condiciones legales ineludibles – y una que ha tenido mucho menor visibilidad. En ese fallo, el máximo tribunal del país ordenó al Gobierno garantizar “procedimientos de queja (…) comprehensivos, independientes, imparciales y vinculados con la evaluación del riesgo”.

A juzgar por casos como el de Mutumbajo, Moreno y otros campesinos en la última década, es justamente lo que el Estado colombiano no ha conseguido implementar hasta hoy.

La larga espera de los Mutumbajoy

De las tres fumigaciones que vio su finca La Esperanza, la que más le arrebató la ilusión a Pedro Pablo Mutumbajoy fue la tercera.

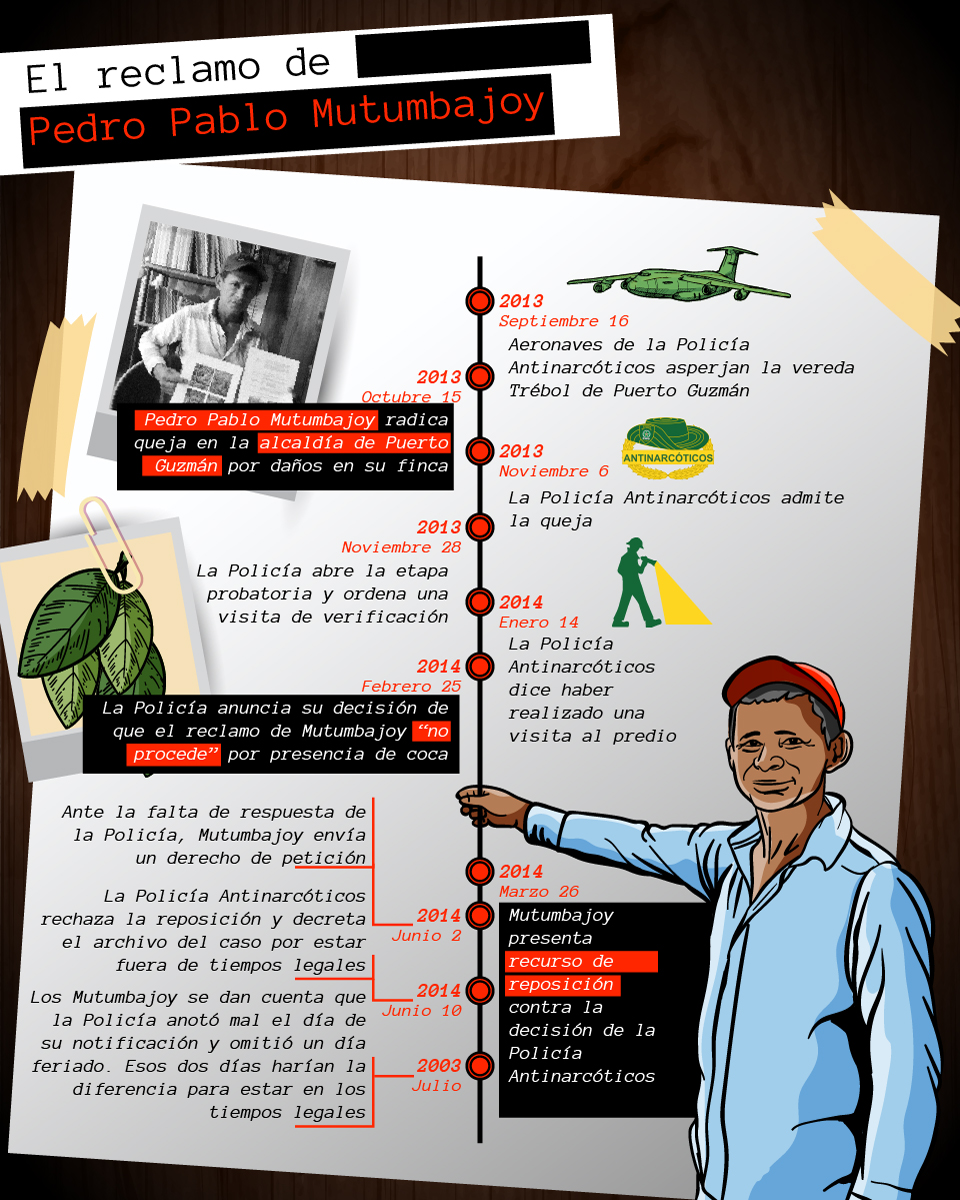

Poco después del almuerzo, entre las 2:30 y las 3 de la tarde del 16 septiembre de 2013, aeronaves de la Policía Antinarcóticos sobrevolaron la vereda El Trébol, a 2,5 kilómetros del pueblo de Puerto Guzmán. Tras percatarse de las secuelas de la aspersión, Pedro Pablo acudió al personero del municipio y, tras enterarse de qué documentos debía reunir para presentar un reclamo formal, preparó su expediente, que esta alianza periodística estudió.

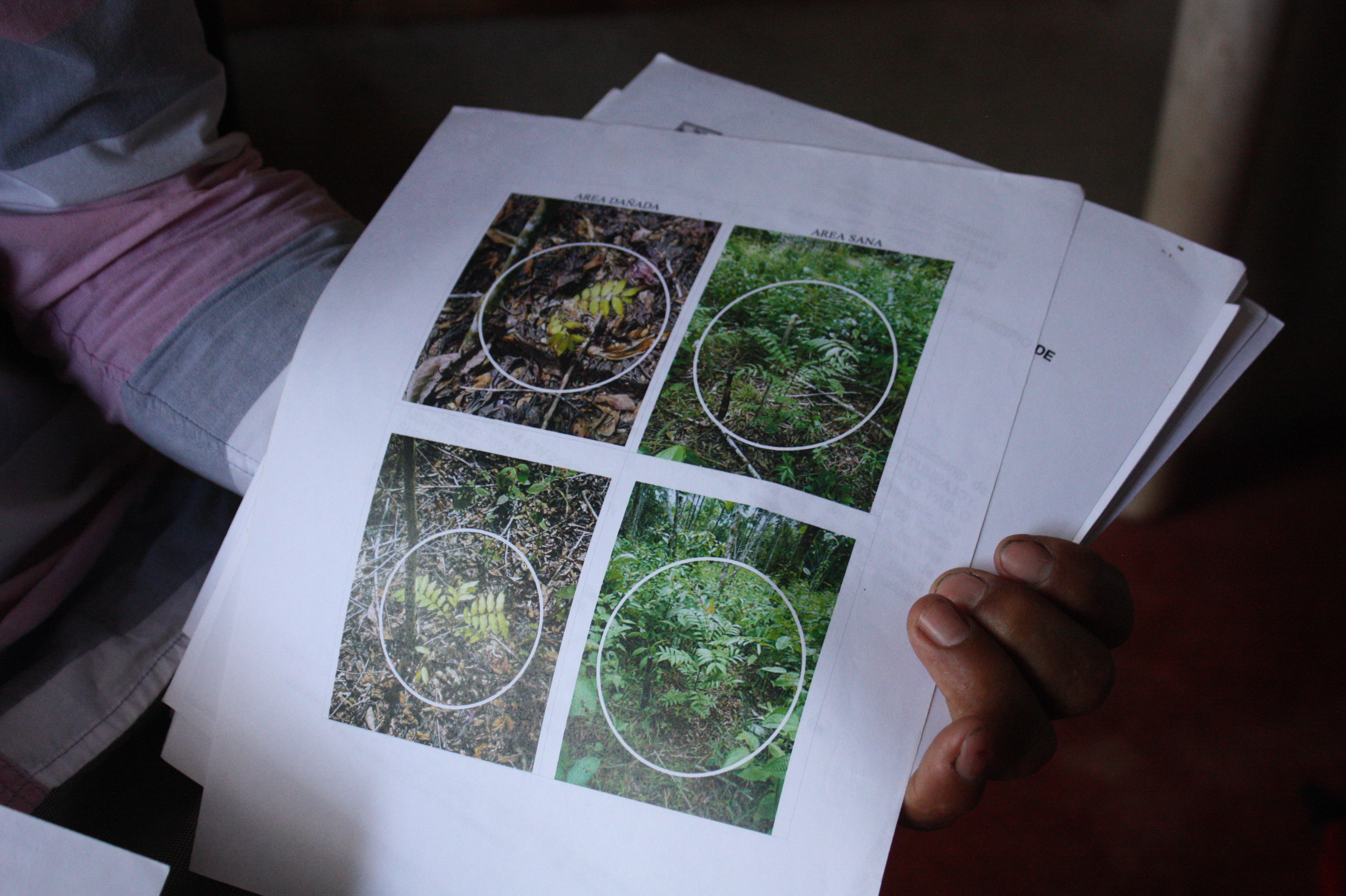

Con ayuda de un ingeniero amigo, hizo un levantamiento, con coordenadas geográficas precisas, del plano de su finca y del cuarto de hectárea de cultivo afectada. Le pidió al secretario de agricultura del municipio un avalúo aproximado de las pérdidas, que éste tasó –usando los precios comerciales de las cinco maderas allí presentes- en 160 millones de pesos (unos 83 mil dólares de la época). Adjuntó fotos de sus aceitunos –llamados taras en Putumayo y palo blanco o simaruba en el mundo maderero- amarillados por el químico, así como de individuos saludables del mismo bosque. Alistó el contrato de donación con el que su madre le había cedido un lote de seis hectáreas de la finca familiar donde se criaron los Mutumbajoy.

En la tarde del 15 de octubre, Pedro Pablo radicó su solicitud ante la alcaldesa encargada, que lo remitió a la Policía Antinarcóticos. “El día 16 del mes de septiembre fueron fumigadas por las avionetas las plantaciones forestales”, dice escuetamente el objeto de la queja.

Tres semanas después, la Policía Antinarcóticos admitió el reclamo y a finales de noviembre abrió la etapa probatoria y ordenó una visita de verificación a La Esperanza. Un mes y medio después, el 14 de enero de 2014, la Policía dice haber inspeccionado el predio de Mutumbajoy – aunque él nunca los vio.

Con esa información, el 25 de febrero, la Policía tomó su decisión de fondo sobre el caso: que el reclamo de Pedro Pablo “no procedía”. Según el auto firmado por el coronel Guillen Alexander Amaya, “se encontró presencia de cultivos ilícitos de coca en la coordenada (polígono) suministrada en la queja” y, en cambio, ninguna “de afectación a causa de las operaciones de aspersión, toda vez que la línea de aspersión se encontraba fuera del polígono reportado por el quejoso”.

Al tiempo que aseguraba que en La Esperanza había coca, la Policía Antinarcóticos negó que los Mutumbajoy tuvieran un cultivo agroforestal. En su decisión, en dos ocasiones, el coronel Amaya subrayó que “no se evidencia la implementación agrícola reportada en la queja”, pero que, en cambio, “se observó bosque nativo en buen estado” – exactamente lo que Pedro Pablo les había contado que tenía sembrado y donde él denunciaba el daño a 350 arbolitos.

La prueba que usó la Policía para argumentar que no había una afectación con glifosato reveló su propia ignorancia de actividades económicas sostenibles recomendadas para la Amazonia por el propio gobierno nacional, distintas a la agricultura o la ganadería extensiva.

Un mes después, el 26 de marzo, Pedro Pablo interpuso un recurso de reposición. “En mi finca no hay una sola mata de coca, ni cultivos de árboles maderables mezclados con coca, no hay objetividad. Porque si bien es cierto que alrededor de mi finca sí existen vecinos que cultivan la coca, no ocurre eso en mi tierra”, le escribió al coronel Mario Gilberto Vargas, pidiéndole una nueva visita que nunca llegaría.

“Sí existen cultivos de árboles maderables en la finca y en los mismos fueron afectados por glifosato. Reitero la necesidad de verificar en terreno lo narrado”, le insistió. Al día de hoy, jura que la coca estaba en un predio colindante, a un centenar de metros de sus árboles, pero jamás en el suyo.

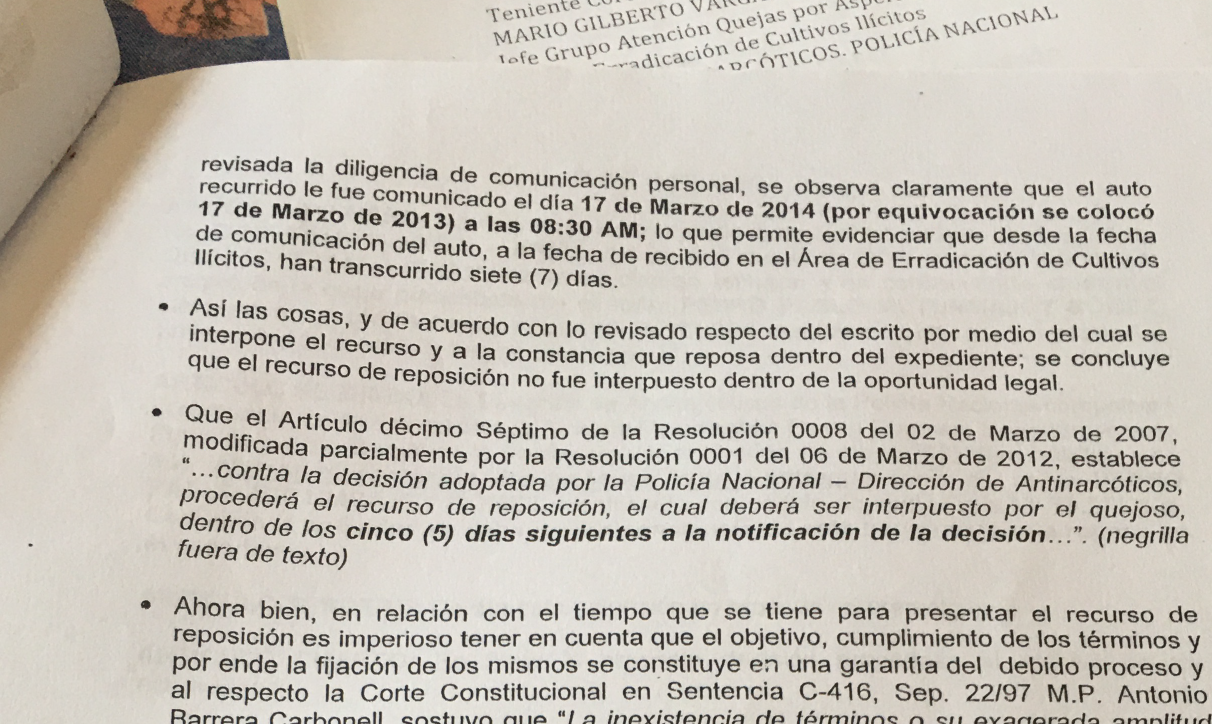

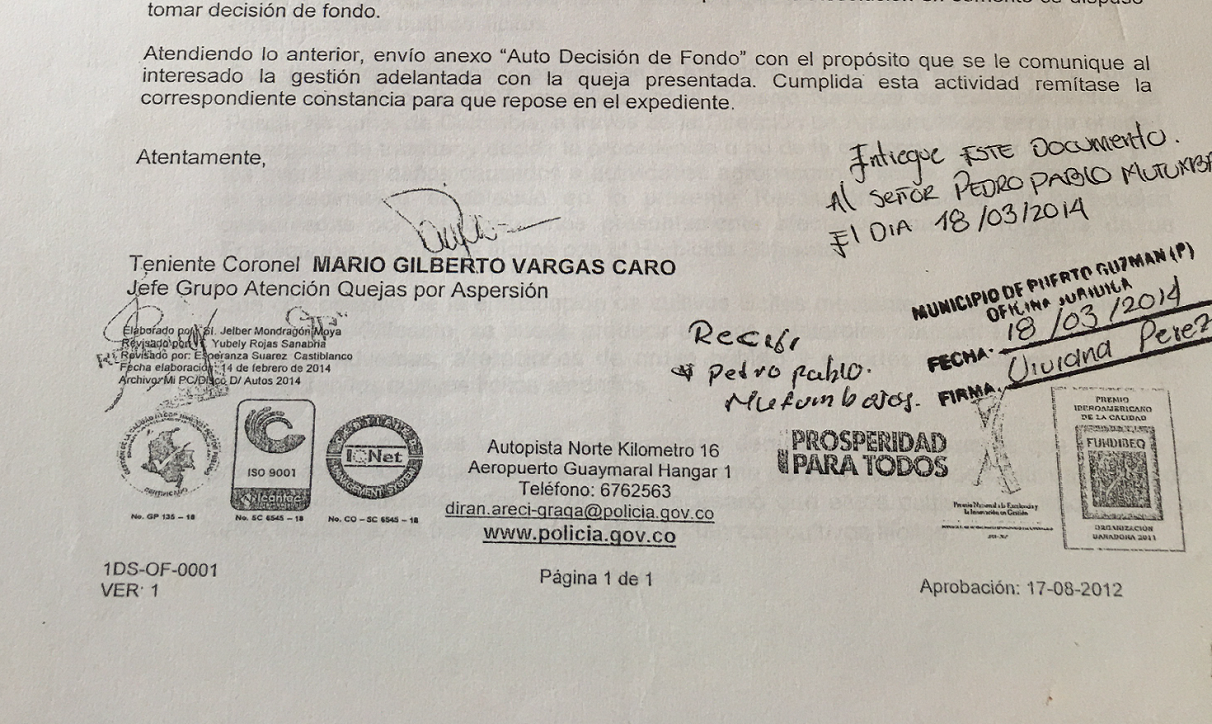

Pasaron dos meses sin ninguna respuesta de la Policía. Finalmente, el 10 de junio y una semana después de un derecho de petición de Mutumbajoy pidiendo noticias, llegó otra carta de Antinarcóticos. Sin entrar en detalles sobre su petición, le anunciaron tajantemente: no se le concedía el recurso porque “no fue interpuesto dentro de la oportunidad legal”. Según la Policía, habían pasado siete días desde que había sido notificado de la decisión de fondo: dos más de los que tenía para pedir una revisión. Por consiguiente, su caso quedaría archivado.

Sin embargo, las cuentas de la Policía estaban mal. Tres anotaciones en la esquina derecha de la carta que le envió el coronel Vargas al alcalde Edison Gerardo Mora, pidiendo notificar al quejoso, revelan una primera equivocación. “Entregué este documento al señor Pedro Pablo Mutumbajoy el día 18/03/2014”, dice una inscripción en bolígrafo negro, encima del sello de la oficina jurídica –con la misma fecha- y el recibido del campesino. Es decir, Pedro Pablo fue notificado un día después de lo que dijo Antinarcóticos.

A esa anomalía se sumó otra: el 24 de marzo fue festivo en conmemoración a San José y uno de los diez feriados que se trasladan al lunes para volverse un fin de semana largo - o ‘puente’ en la jerga colombiana. Por lo tanto, no era un día hábil.

Esos dos errores, esos dos días, significaban que la solicitud de los Mutumbajoy no se había demorado siete días, sino cinco. Siempre estuvo en los tiempos correctos.

Irónicamente, al tiempo que la queja de Mutumbajoy se perdía en el laberinto burocrático, el gobierno de Juan Manuel Santos estaba en La Habana negociando el capítulo sobre política de drogas del Acuerdo de paz, que subraya que los campesinos son uno de los eslabones más débiles de la cadena del narcotráfico, prioriza la sustitución de coca para brindarles soluciones y mantiene la aspersión aérea solo como última opción.

Los negociadores del Gobierno y la guerrilla de las Farc se sentaron a hablar del tema por primera vez el 28 de noviembre de 2013, justo el mismo día en que la Policía ordenó visitar la finca de Pedro Pablo. A mediados de mayo, las dos partes anunciaron que habían llegado a un acuerdo sobre el tema, el tercero en el camino que conduciría al apretón de manos final y al desarme de la guerrilla más antigua de las Américas. Solo tres semanas después, el recurso de Mutumbajoy fue negado de plano, sin derecho a pataleo.

Una segunda Esperanza

La Esperanza fue un cocal durante casi dos décadas. Lo era ya en 1990, cuando la familia Mutumbajoy –de raíces indígenas y originaria del resguardo inga de Yunguillo, en la montañosa frontera entre Cauca y Putumayo- compró la finca.

Ellos vivieron de la coca por trece años, acompañándola con yuca y plátano para el diario vivir. “Uno cultivaba en conjunto. Sería mentiroso decir que la gente no vivía de la coca”, dice Pedro Pablo. En esa época Puerto Guzmán, ubicado en las riberas del río Caquetá, tenía grandes extensiones de coca sembrada: en su pico más alto, en 1999, tuvo casi 8 mil hectáreas y ocupaba el sexto lugar en toda Colombia, según datos de la ONU.

Tras las dos primeras fumigaciones, que ellos fechan en una misma semana de 2003, intentaron sembrar otros cultivos sin éxito. Los plátanos, recuentan, crecieron un metro para luego secarse, la yuca se amarillaba y el maíz nunca se dio. Lo atribuyeron a la mala calidad del suelo, degradado tanto por el glifosato caído del cielo como por la decena de agroquímicos –organofosforados, oxicloruro de cobre, carbendazim, paraquat y glifosato- que le echaban a la coca. Al final dejaron el predio abandonado durante siete años.

Hasta que volvieron para intentar algo muy distinto hacia el 2010, en un tránsito que Pedro Pablo atribuye, por partes iguales, a la disuasión que les quedó de la fumigación, a una idea que vio en el programa de televisión del Profesor Yarumo que no se perdía y a los cálculos financieros que fue madurando. Sembraría árboles maderables nativos.

“Los cambios siempre son de números”, dice, sentado en su casa de madera en el pueblo mientras rememora los suyos. Cuenta que cuando llegaron a la finca donde se crió, había un pequeño tara de medio metro que, dos décadas después, creció y dio 15 piezas de madera. Hizo cuentas mentales: si cada tablón grueso se pagaba a 15 mil pesos, podría –al cabo de dos décadas- recaudar más de 300 mil pesos por árbol. En su cabeza pesaba otra cuenta: si en su infancia la madera se recolectaba en las inmediaciones de Puerto Guzmán, desde hacía una década ya la traían de cuatro horas de distancia.

No tuvieron apoyo, quizás porque no era una transición inmediata de la coca a otra actividad lícita, quizás porque el Estado colombiano históricamente ha tenido una visión muy acotada de qué es un proyecto productivo, o tal vez porque la sustitución de coca está entre los rubros a los que menos plata se le destina de toda la política de drogas en Colombia. El presupuesto antinarcóticos de 2010, el último que se ha hecho público y casi simultáneo a los primeros intentos de Pedro Pablo por sembrar maderables, muestra que por cada peso invertido en iniciativas de desarrollo alternativo, se iban 11,5 a la estrategia de reducción de la oferta de drogas en la que la fumigación siempre fue la consentida.

Así que la siembra y el cuidado los hicieron, en palabras de Pedro Pablo, “a fuerza propia”. Pidieron un crédito en el Banco Agrario, pero se lo negaron por no tener la escritura del predio sino –como es común en Putumayo y buena parte del campo colombiano- apenas una posesión informal de un predio.

“Sembrar los árboles fue un trabajo ni el verraco: primero hacer el semillero, cuidándolos como una niña bonita, sembrándolos con todo el amor, para que lleguen a fumigar sin darse cuenta qué es lo que fumigan. Es algo injusto, porque fue un cambio de vida de la coca a los árboles”, dice su esposa Jenny Vargas. Para ella no fue fácil. Por años fue escéptica de que pudieran vivir de la madera. “Yo no le miraba gracia a sembrar árboles: ¿cuántos años para que me dé resultados? Yo lo veía como tirar una piedra al río”, dice, mientras cocina un sancocho para el almuerzo.

Hoy se ríen de ese plan, que ya ven como una herencia para sus cuatro hijos y dos nietos. Hace unas semanas, cuando Jenny acompañó a Pedro Pablo a sembrar mil plántulas de achapo, le preguntó cuánto demorarían en crecer. “En 120 años vamos a venir a aprovecharlos”, le dijo su esposo muy serio, aunque en broma. Estaba multiplicando por cinco el tiempo real. “No estará ni el polvillo de los huesos”, le respondió ella riendo.

Ocho años después de la fumigación, casi veinte después de dejar la coca, la finca de los Mutumbajoy parece un jardín botánico: ellos calculan que hay unos 10 mil árboles. Todos son nativos de la cuenca amazónica, todos son fuente de maderas preciadas para muebles y pisos, pero talables sin perjudicar el bosque.

Hay achapos y taras de rápido crecimiento, cosa de dos o tres décadas, mientras otros -como robles y ahumados- demorarán más de medio siglo. Pedro Pablo va saltando por toda La Esperanza señalándolos de memoria: cominos, juansocos, perillos, arenillos, morochillos, canaletes, inches, arracachos, sangres de toro y madroños de chuquia, más algunas palmas silvestres de asaí, milpeso y canangucha cuyos frutos podrá cosechar también.

El experimento personal de los Mutumbajoy es un ejemplo del tipo de soluciones que pueden servirle a campesinos de la Amazonia colombiana que intentan salir de la coca, dándoles opciones económicas y al mismo tiempo garantizando que éstas, a diferencia de la ganadería extensiva, sí son ambientalmente sostenibles.

Porque en este rincón del sur del país se juntan al menos dos problemas graves. Aunque Puerto Guzmán tiene hoy 1.063 hectáreas de coca, o una octava parte de lo que tuvo hace veinte años, Putumayo sigue siendo el tercer departamento con mayor extensión de este cultivo en el país. Al mismo tiempo, el municipio donde tienen su finca ha estado de manera consistente entre los 15 con mayor deforestación en Colombia y solo en 2019 perdió 4 mil hectáreas de bosque –o 2 por ciento del total nacional talado- según el Ideam. Entre los árboles de La Esperanza se ven ya madrigueras de armadillos, una señal de que la biodiversidad está llegando a habitar el sombreado bosque.

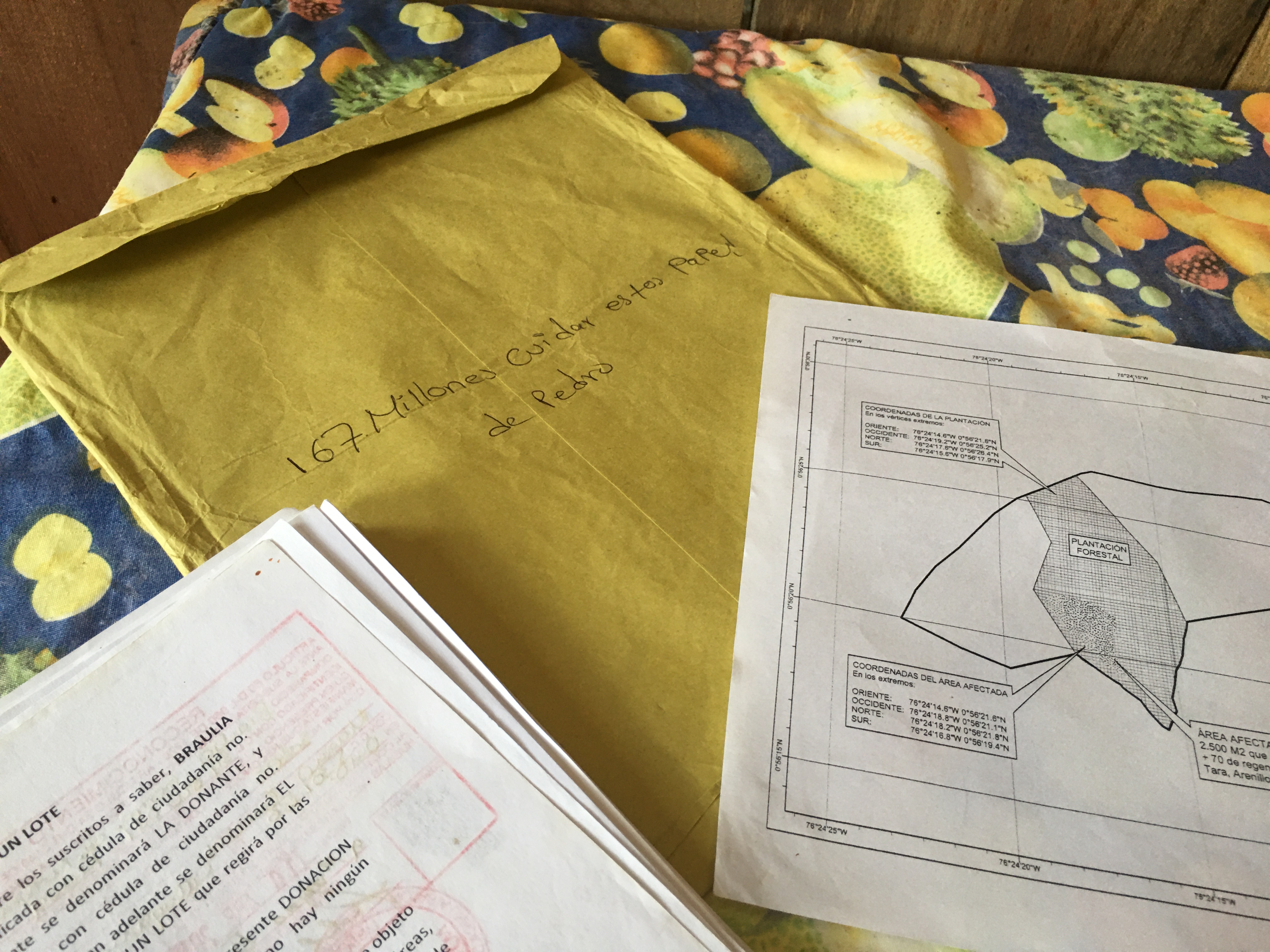

Aunque Jenny era partidaria de tirar los documentos del reclamo, frustrada por lo que percibía como la indolencia del Estado, Pedro Pablo decidió guardarlos. Aún hoy permanecen en un estante de su casa, doblemente protegidos por un sobre de manila y una carpeta de plástico. Un letrero a mano advierte: “167 millones: cuidar este papel de Pedro”.

La policía: juez y parte

Desde el inicio de la fumigación de coca a gran escala con el Plan Colombia, la mayor asistencia militar y económica que Estados Unidos le ha dado al país en su historia, se sabía que el glifosato podía caer donde no debía. Es por esto que desde entonces se hablaba de la importancia de tener los “mecanismos más apropiados para la atención de quejas que se interpongan por posibles afectaciones”, como subraya el plan de manejo ambiental del programa desde 2003.

Su primera versión es de octubre de 2001, cuando el Consejo Nacional de Estupefacientes –una instancia de gobierno que reúne a los los ministerios a cargo de la política de drogas, a los organismos de control y a la Policía- creó el procedimiento para reportar “efectos colaterales que afecten los cultivos lícitos aledaños”.

Según esa resolución, los campesinos podrían ir donde el personero de su municipio a interponer quejas por daños a cultivos legales, máximo 60 días después de la aspersión, que serían luego enviadas a la Dirección Antinarcóticos de la Policía Nacional y a la ya extinta Dirección Nacional de Estupefacientes. Cada reclamo, que podía presentarse por escrito u oralmente, debía incluir la ubicación de la finca, la relación de los daños, información sobre la actividad productiva perjudicada, una copia de la escritura o prueba de posesión del predio, los datos sobre el operativo de fumigación y pruebas que soportaran la petición. Quien tuviese cultivos de coca quedaría excluido.

Prometía que sería un “procedimiento expedito”. Tenía tiempos precisos para cada etapa: la Policía Antinarcóticos tenía cinco días para comprobar si había realizado aspersiones en la zona y luego diez para hacer una visita de campo. Si concluía que había daños, los reconocería por escrito y estimaría un monto de compensación, pero si no, tenía dos días para comunicar su decisión.

En la vida real, esos tiempos resultaron ilusorios. Como muestra el archivo del caso de Pedro Pablo Moreno en el sur de Bolívar, un reclamo podía demorarse once meses en ser admitido, un año en tener una visita de campo y casi tres años en emitir una decisión de fondo.

Al final, la mayoría de las quejas ha sido negada. De 2265 quejas presentadas por campesinos en Putumayo entre 2001 y 2015, un 93,5% fue rechazada por la Policía, según una investigación de la antropóloga cultural colombo-estadounidense Kristina Lyons publicada en la revista académica Social Studies of Science. Encontró un patrón similar en el país: un 96% de 17.463 reclamos habría sido negado en ese mismo período, que corresponde a los gobiernos de Andrés Pastrana, Álvaro Uribe y Juan Manuel Santos, según cifras de la propia Policía.

Lyons también documentó el recorrido de 70 quejas radicadas en la oficina jurídica de la alcaldía de Puerto Guzmán a partir de 2011 y concluyó que había una “sistemática denegación” de éstas. En su análisis de los reclamos, enumeró los argumentos más frecuentes para desestimar las solicitudes: entregas fuera de los tiempos legales, coordenadas incompletas, “falta de causalidad” entre operativos y daños, discrepancia de fechas y horas con registros de sobrevuelos y existencia de cocales dentro de los predios.

“El sistema no contempla la realidad de las personas fumigadas”, dijo a esta alianza periodística Lyons, quien es profesora de la Universidad de Pensilvania y lleva una década haciendo trabajo de campo en Putumayo. “Si la gente vive lejos o no tiene cómo georreferenciar su finca, queda fuera de los tiempos. Cuando hay presencia de grupos armados ilegales en la zona, que les impiden sacar fotos o llevar un GPS, su queja queda marcada como ‘desistida’. Está diseñado para obstaculizar el acceso a la justicia”. En su visión, presentar un reclamo implica una sincronización de documentos, trámites y herramientas que rara vez están al alcance de los campesinos en zonas rurales apartadas.

En el caso de Mutumbajoy, sacar las coordenadas no habría sido posible sin los equipos y el tiempo de su amigo Jorge Luis Guzmán, un ingeniero de sistemas con maestría en Chile que regresó hace unos años al pueblo que lleva el apellido de su padre, el colono que lo fundó en los años setenta.

“Si Pedro Pablo no tuviera un amigo que manejara los aparatos, le habría quedado mucho más difícil la documentación. Y si viviera cuatro horas hacia adentro, a mí tampoco me habría sido posible ayudarlo”, dice Jorge Luis, quien tiene un cultivo agroforestal y lidera una escuela audiovisual para jóvenes desde la fundación familiar Itarka. A Guzmán y Mutumbajoy les tomó una semana recorrer el predio tomando fotos con el ‘tracking’ de las coordenadas, bajarlas con el software ArcGIS y asignárselas al plano de la finca en Google Earth. En total, fueron 26 horas de trabajo, según la bitácora que el ingeniero aún guarda.

Para Lyons, también resulta problemático que los equipos que evalúan las quejas suelen sobrevolar los predios y no conversan con los reclamantes. “Como no bajan a la tierra y no hablan con la gente, no puedes siquiera verificar que vinieron a evaluar los daños y tampoco tienen que mostrarte la evidencia”, dice, describiendo el aparato de investigación como opaco y arbitrario.

Ese sistema de reclamos vio algunos cambios a lo largo de los años. Una nueva resolución del Consejo Nacional de Estupefacientes de 2007 creó un formato estandarizado para que las alcaldías pudieran registrar las quejas, clarificó los tiempos de respuesta en cada una de las etapas y creó un “grupo técnico interinstitucional especial” para verificarlas, trabajo que en todo caso siguió liderando la Policía Antinarcóticos. También redujo el calendario para presentarlas a la tercera parte: en vez de 60 días desde las ‘fumigas’, como las suelen llamar los campesinos, pasaron a tener 20 para radicar su petición. Cinco años después, otra resolución amplió los tiempos a 30 días para instaurar la queja.

El problema estructural, sin embargo, permaneció constante: durante dos décadas, la Policía Antinarcóticos fue la responsable de examinar y evaluar la seriedad de las quejas presentadas contra el comportamiento de ese propio cuerpo policial. Es decir, era juez y parte.

El regaño de la Corte Constitucional

El problema resurgió durante el debate en la Corte Constitucional, a raíz de la demanda de varias comunidades afro del Chocó que pidieron respetar su derecho a la consulta previa y exigieron indemnizaciones por los daños que les causó el glifosato.

Al darles la razón en abril de 2017, la Corte subrayó tres fallas significativas en el sistema de quejas y reclamos. Primero, señaló que requisitos como la georreferenciación de los predios había sido un obstáculo para que los campesinos accedieran a la justicia. Segundo, observó que el hecho de que la Policía fuese juez y parte “no ofrece garantías de independencia e imparcialidad”. Por último, señaló que no había evidencia de que las 158 quejas que sí fueron compensadas entre 2012 y 2015 –de un universo de 3.090 solicitudes, según los datos de Antinarcóticos- hayan sido tomadas como lecciones aprendidas y condujeran a cambios.

Varias entidades coincidieron con ese diagnóstico. La Procuraduría General de la Nación advirtió a la Corte que “la dificultad de tener un equipo GPS en una zona de conflicto armado o la carencia de planos adecuados en los municipios (…) pueden generar datos errados y rechazo injusto de la reclamación”.

Kristina Lyons fue una de las personas que pidió a la Corte volver más estrictas las condiciones del sistema de reclamos. “Vale la pena preguntarse si, ante la cantidad de quejas rechazadas al nivel regional y nacional, si el mecanismo para tramitar estas quejas por daños originados en las operaciones de aspersiones aéreas con glifosato ha cumplido con los estándares constitucionales, como el derecho al debido proceso administrativo y la protección a los sujetos de especial protección constitucional como son las comunidades indígenas, campesinas y afro-descendientes”, le dijo a los magistrados durante una audiencia pública de seguimiento al fallo en 2019.

Como ejemplo de esas fallas en el debido proceso, Lyons les relató la historia de Pedro Pablo Mutumbajoy y del limbo en el que, pese a los errores administrativos de la Policía, quedó su queja.

Más allá de los casos individuales, las fallas en estos canales de comunicación, la inexistencia de una instancia independiente para decidir los casos y la falta de respuestas transparentes podría estar debilitando la percepción que tienen sobre el Estado los campesinos en zonas cocaleras. “En la medida en que las instituciones no cumplen las expectativas de los ciudadanos sobre aquello para lo que fueron creadas, eso contribuye a minar su legitimidad, porque en últimas construimos confianza por resultados”, dice Miguel García Sánchez, profesor de la Universidad de los Andes que hace una década investigó la relación entre el negocio de la droga y la cultura política local. Su conclusión fue que la erradicación -y en particular la aspersión- tienen consecuencias negativas en la participación y confianza ciudadanas en las instituciones.

Esta alianza periodística solicitó a la Policía Antinarcóticos información sobre el estado de los reclamos de los Moreno y los Mutumbajoy, pero a la fecha de publicación no había respondido las peticiones.

La burocracia frustra al otro Pedro Pablo

El campesino de idéntico nombre, Pedro Pablo, pero de distinto apellido, Moreno, duró una década dando una pelea administrativa similar por una fumigación errada sobre sus cultivos en el otro extremo del país. Al igual que su tocayo putumayense, Moreno tampoco logró una respuesta de fondo a su queja.

No lo consiguió pese a que figuras tan respetadas como el sacerdote jesuita Francisco de Roux –hoy presidente de la Comisión de la Verdad y en esa época un conocido promotor de proyectos económicos y de reconciliación en el Magdalena Medio- le escribieron hasta a la entonces primera dama Lina Moreno, esposa del presidente Álvaro Uribe, exponiendo un caso que veían como una injusticia.

El 12 de junio de 2003, Moreno fue al pueblo de Simití a radicar su queja. En el documento, que el campesino llenó a mano y que luego el personero municipal pasó a máquina de escribir, quedaron pocos detalles del suceso pero sí un relato pormenorizado de sus consecuencias y su solicitud de indemnización.

A mediados de mayo, denunció Moreno, aeronaves asperjaron su finca La Morena en la vereda Humaderita de Simití, una zona de difícil acceso ubicada en medio de ciénagas y humedales interconectados que hacen que esa zona del Magdalena Medio sea una de las mejores exponentes de lo que los científicos llaman ‘la Colombia anfibia’. Era la época en que, en el marco del Plan Colombia, el gobierno de Estados Unidos financiaba el programa de aspersión y empresas de ese país como DynCorp eran contratadas para llevarlas a cabo.

“Le hago saber que estos son los daños causados por la fumigación”, escribió Pedro Pablo, “afectando más de 30 años de patrimonio que con esfuerzo se ha trabajado con la familia hemos conseguido”. Acto seguido, presentó el catálogo de pérdidas: 6 mil palos de yuca, 200 ñames, 300 mafafas, 300 plátanos, cinco hectáreas de maíz y dos y media de arroz, 300 cañas de azúcar, 20 piñas, 50 árboles de aguacate y 100 de cítricos, además de cuatro hectáreas de maderables, 15 de pasto braquiaria y el jardín de su casa.

En este punto parecería haber un bache en el archivo que guardó Pedro Pablo –cuya copia le entregó al Colectivo de Abogados José Alvear Restrepo (Cajar) y que esta alianza periodística revisó- porque no hay ningún documento durante un año entero. Quizás nunca lo hubo porque, en julio de 2004, Moreno envió un derecho de petición a la Policía Antinarcóticos y a la Dirección Nacional de Estupefacientes preguntando si había avances en su caso. “Yo soy una persona temerosa de Dios y espero en él que usted tome la mejor decisión”, les escribió.

Probablemente nunca se enteró de que la Policía sí había admitido su queja en mayo, casi un año tras presentarla, según se desprende de documentos posteriores. Este hecho devela la pobre comunicación de la entidad con quienes presentaban quejas formales por su actuación.

En febrero de 2006, casi tres años después de la fumigación por la que se quejó Moreno, la Policía Antinarcóticos finalmente tomó una decisión: pese a confirmar que el 26 de mayo de 2003 sí hubo operativos de aspersión en Simití, el coronel Henry Gamboa –jefe del área de erradicación- anunció que la queja “no procedía”.

Según el acta que envió al personero local, la policía hizo una “visita de campo” al predio entre el 18 y el 22 de agosto del año anterior. “Se encontraron varios lotes con coca en medio del bosque nativo que fueron objeto de aspersión aérea”, decía el reporte de Antinarcóticos. “Estos se encuentran mezclados con algunas matas de plátano y yuca, deforestación continua para nuevas siembras, razón por la cual el grupo decidió rechazar la queja al haberse encontrado presencia de remanentes de plantaciones de coca mezclados con cultivos lícitos de pancoger”. Tras categorizar su finca como un “cultivo mezclado” -o “aquella siembra que presenta plantas lícitas e ilícitas”-, rechazaron el reclamo y ordenaron su archivo.

Sin embargo, esto tampoco llegó a oídos de Moreno. Medio año después de la carta de Gamboa y el día en que se cumplía un año exacto de la visita que la Policía dijo haber hecho a su predio, Pedro Pablo envió una carta a Antinarcóticos preguntando por su caso.

En su misiva de agosto de 2006, enviada con el membrete de la personería de Simití, Moreno expresó al coronel Gamboa su extrañeza por los avances que tuvo su caso desde hacía un año, pues ellos no habían sabido de ninguno de ellos. Le contó que se quedaron esperando la visita al predio y que, tras preguntarle al mayor Edgar Efrén Pérez, él les dijo que ya había ocurrido un año atrás. También le dice haberse recién enterado del cierre del caso. “No sabíamos nada de la decisión tomada por ustedes, porque el señor personero municipal de Simití, por seguridad, no puede enviar a esta zona y el único medio con que cuenta es la emisora comunitaria y ninguna persona conocida nos había informado al respecto”, escribió, revelando las fallas en la notificación a quienes interponían quejas.

Pero, por encima de todo, Pedro Pablo Moreno se mostró perplejo y molesto por la conclusión de la Policía de que había coca en su terreno. “Se nos hace extraño que ustedes manifiesten que en nuestra finca habían vestigios de cultivos ilícitos, donde nosotros somos una familia cristiana temerosa de Dios y que nunca nos hemos mezclado con negocios de narcotráfico porque esto atenta con nuestros principios religiosos”, escribió. Insistió en que no tenían ninguna información de la visita de verificación de la Policía, por lo que les solicitó una copia del acta de la visita y datos sobre quién los recibió en el predio.

No había pasado siquiera un mes desde su queja por el reclamo cuya respuesta no conocieron, cuando los Moreno se vieron inmersos en otro operativo de fumigación. El 19 de septiembre de 2006, a eso de las 2:10 de la tarde, dos aeronaves de la Policía Antinarcóticos sobrevolaron la finca La Morena y por segunda vez dejaron caer glifosato, según el relato que hizo Pedro Pablo en su carta a la Policía Antinarcóticos.

Esta vez, añadió una nueva preocupación: había recibido un crédito de 5 millones de pesos (unos 2100 dólares en aquel entonces) del Banco Agrario. “Al ser fumigada mi finca, ¿cómo le voy a pagar al banco?”, le preguntó al coronel Gamboa.

Quizás frustrado por la falta de respuestas claras en su primer reclamo, esta vez al campesino de Simití lo acompañó un grupo variopinto de conocidos que escribió a las autoridades con testimonios de su talante. Quince vecinos recalcaron que, en sus palabras, “esta finca no ha tenido cultivos ilícitos” y respaldaron un cuadro que describía la nueva estela de daños: 120 palos de cacao, árboles de aguacate, mango y cítricos, matas de bore y yuca y una treintena de maderables nativos. El reverendo Andrés Marimón, pastor de la Iglesia Cristiana Cuadrangular de Pozo Azul, escribió al coronel Gamboa de Antinarcóticos para dar fe de que Moreno era feligrés suyo y que “nunca ha trabajado con cultivos ilícitos”. Y los integrantes de la junta de acción comunal, a la que pertenece Pedro Pablo, pidieron al personero corroborar que en La Morena no había coca.

Una semana después, el entonces personero Juan Carlos Torres viajó a La Morena, a unas dos horas del pueblo. Como resultado de esa visita, expidió un acta en donde certificó que su dueño “no tiene en su finca ningún cultivo ilícito y que los daños causados por la fumigación anteriormente son muy ciertas”.

Nada de esto pareció llevar a la Policía a revisar su postura. El 24 de octubre, un mes después de la segunda fumigación denunciada por Moreno, Antinarcóticos respondió a su carta sobre la primera. En ella, el coronel Gamboa reiteró el diagnóstico de su visita y culpó al personero de Simití de cualquier demora en la notificación. “Se concluyó que las coordenadas son las mismas que se visitaron (…), razón por la cual se mantendrá lo decidido por parte del grupo de quejas”, remató.

Subiendo el caso a la primera dama

Ante la poca disposición de Antinarcóticos de revaluar su rechazo, la familia Moreno cambió de estrategia: empezó a enviar cartas y buscar reuniones con diversas instancias del gobierno de Álvaro Uribe, incluida su esposa –y tocaya de apellido- Lina Moreno.

Lo hicieron con apoyo del Programa de Desarrollo y Paz del Magdalena Medio, un experimento que ha promovido decenas de proyectos de economía campesina y créditos asociativos -como alternativas económicas en medio de la guerra- en una zona de 30 mil kilómetros cuadrados que abarca 29 municipios rurales de Santander, Cesar, Antioquia y Bolívar, incluyendo el rincón de Simití donde los Moreno viven.

En febrero de 2007, uno de los hijos de Pedro Pablo escribió una carta de tres páginas al Ministro del Interior Carlos Holguín Sardi pidiéndole una revisión del proceso. En ella, Javier Elías Moreno le contó la historia de su queja frustrada y de la segunda fumigación, pero también la retorcida manera cómo la familia se enteró de las decisiones administrativas tomadas en su contra. Según su relato, Elías aprovechó una invitación que le hicieron a Cimitarra (Santander) en julio de 2006, como parte de un grupo de líderes sociales del Magdalena Medio, para llevar su archivo personal. Allá le presentaron a la primera dama Lina Moreno, quien tras oír su caso lo conectó enseguida con el ex congresista Luis Alfonso Hoyos, quien entonces dirigía la Agencia Presidencial para la Acción Social que agrupaba los programas sociales del gobierno. Fue Hoyos quien le ayudó, vía fax, a conseguir la decisión de Antinarcóticos en su contra.

“Pedimos ya no solo porque se nos reconozcan los daños causados en la parte económica, sino por la dignidad de nuestra familia que nos resuelvan el caso lo más pronto posible y que se retracten de las afirmaciones de que somos cocaleros, pues esto nos va a traer consecuencias más graves que la fumigación, como es la expropiación y la amenaza de grupos armados a nuestra familia”, imploró Moreno al ministro, apenas un mes antes de que éste firmara la resolución que fijó tiempos más perentorios a la evaluación de los reclamos.

En la carta, le contó a Holguín Sardi que ellos creían que la Policía nunca inspeccionó el predio y que jamás les proporcionó copia del acta. Le dijo que ellos creían que Antinarcóticos tenía coordenadas erradas del predio, porque Fupad – una ong afiliada a la OEA con la que trabajaron- lo había georreferenciado y estableció que la coca en predios vecinos estaba a 500 a 800 metros de distancia. Le explicó que, en una entrevista con el coronel Gamboa en la base aérea de Catam en Bogotá, éste adujo que la Policía no tenía su segunda queja, que no había recibido su pedido del acta y que solo procedía interponer una demanda legal. Y que prometieron organizar un nuevo sobrevuelo para evaluar la segunda queja, en el cual Javier solicitó que la familia pudiese estar presente.

“Si nosotros que hemos resistido a los ataques de la guerrilla (nos han matado dos hermanos), de los paras (pues nos amenazaron y nos robaron las pocas vaquitas adquiridas en 40 años de trabajo de mi padre y nos señalaron de guerrilleros, teniendo que desplazarse otro hermano), ahora es el mismo Estado el que nos va a desplazar con otra fumigación”, cerró su carta, que envió con copia a la primera dama y a Hoyos.

Seis meses después, el padre Francisco de Roux -fundador del Programa de Desarrollo y Paz- también intercedió por los Moreno. En agosto de 2007, envió una dura carta al coronel Gamboa expresándole su “enérgica protesta por el trato” del policía antinarcóticos a Javier Elías en una segunda reunión realizada unas semanas atrás, esta vez en el Ministerio de Agricultura, de la que él y su mano derecha Miriam Villegas fueron testigos.

Según el sacerdote jesuita, ese día el máximo responsable de la atención a los reclamos “trató al campesino de mentiroso” y lo culpó de los costos de los dos sobrevuelos, por haberles supuestamente entregado coordenadas erróneas. De Roux les reclamó que, pese a las certificaciones de varios terceros que recorrieron la finca sin encontrar coca, la Policía Antinarcóticos no quiso siquiera contarle a Elías Moreno qué habían concluido en el segundo sobrevuelo, en el que éste los había acompañado.

“Usted bien sabe que este campesino ha gastado plata de donde no la tiene para hacer viajes a Bogotá buscando todo tipo de certificaciones y muchas entrevistas”, dijo el padre de Roux en la carta en que también copió a la primera dama y en la que les pidió que, al menos, le permitieran “rehacer su buen nombre”. Pero, a pesar de la carta del sacerdote y del “ruego especial de una revisión del caso” de Sandra Devia, directora de asuntos territoriales y orden público del Ministerio de Interior, el caso durmió el sueño de los justos en la Policía Antinarcóticos. En palabras de Pedro Pablo, ésta “cerró el caso sin darnos derecho a réplica u otra oportunidad de defendernos”.

“De nada de eso tuvimos respuesta. Yo no seguí insistiendo después de eso porque se notó que no tenían interés”, cuenta Elías Moreno, hoy, a los casi 19 años de la queja original.

La segunda vez que los fumigaron los Moreno tuvieron mayores pérdidas. Para esa época eran parte, a través de su madre Jóvita Espinosa, de un proyecto productivo de cacao gestionado por la cooperativa local Asocazul, apoyado por el Programa de Desarrollo y Paz del Magdalena Medio y financiado parcialmente por un crédito bancario. Después de que varios de los beneficiarios fuesen fumigados y que sintieran que sus quejas nunca fueron atendidas, una treintena de ellos se unieron en 2013 para presentar –con apoyo del Colectivo de Abogados José Alvear Restrepo (Cajar)- una acción de grupo en la que exigen al Estado colombiano indemnizarles por los daños, como contó Agencia Baudó en este reportaje.

“Al campesino de a pie que coloca su queja no se le escucha. No hay apoyo del Estado nacional, pero tampoco de las administraciones locales. Muchas veces nos tocó ponerles transporte [a los predios] o nos decían que no podían ir por orden público, cuando no es un favor sino su deber”, dice Esther Julia Cruz, campesina y representante legal de Asocazul.

Tras ocho años y un fallo adverso de primera instancia en el Tribunal Administrativo de Bolívar, su demanda finalmente llegó al Consejo de Estado. Teóricamente se debería fallar pronto, ya que en marzo del año pasado esa misma corte decidió una solicitud de prelación a favor de los campesinos, dado que varios son de edad avanzada o están enfermos.

De hecho, su mamá Jóvita murió hace ocho meses, a punto de cumplir 80 años y esperando esa sentencia. Su papá Pedro Pablo, que aún vive en La Morena, tiene 81.

Al igual que su tocayo de Simití, Pedro Pablo Mutumbajoy también depositó su confianza en un abogado. Como no recibió noticias de la Policía Antinarcóticos desde 2014, aceptó la oferta de un veterano político, el ex gobernador encargado Fabián Belnavis, de representarlo legalmente a él y a una veintena de campesinos de Puerto Guzmán a cambio de una comisión sobre cualquier indemnización pagada. Seis años después, sin embargo, Mutumbajoy dice no haber vuelto a oír de él. Consultado por el estado del proceso, Belnavis le dijo a esta alianza periodística que la acción de grupo que presentó en 2015 fue rechazada por el Tribunal Administrativo de Nariño.

Pedro Pablo sigue, en todo, caso insistiendo en que no tenía coca cuando lo asperjaron. “No sé si habrían hecho la visita satelitalmente, pero tienen que tener una imagen que pueden sacar en una pantalla. A mí no me han mostrado esas imágenes que tenemos cultivos de coca”, dice Mutumbajoy, mientras recorre el bosque privado con el que cambió su vida.

Si en los siete meses de gobierno que le quedan, Iván Duque aún quiere insistir en resucitar la fumigación con glifosato, aún cuando la política de drogas de Estados Unidos hacia Colombia viene cambiando bajo Joe Biden y ya no menciona la aspersión aérea, deberá probar que existe un mecanismo efectivo que pueda responder a los reclamos de los campesinos que sufren los efectos colaterales en sus fincas.

En abril de este año, su gobierno dio los primeros pasos hacia un vuelco en el procedimiento de quejas. A partir de ahora, según planteó un decreto presidencial, serán distintas entidades del gobierno las que las evaluarán según la naturaleza del daño reportado. En el caso de afectaciones a cultivos lícitos ya no será la Policía Antinarcóticos, sino el Instituto Colombiano Agropecuario (ICA) que vela por los estándares fitosanitarios del país, mientras que el Fondo Nacional de Vivienda examinará los daños a casas o edificaciones.

Aunque ya no habrá una parte que actúa también como juez, el gobierno deberá en todo caso probar que el mecanismo remodelado realmente escuchará las voces de los campesinos y les responderá dentro de tiempos razonables.

“Yo me siento frustrado. No sienten las necesidades del trabajo que uno hace. Uno está aportando a la sociedad: esos árboles están capturando el CO2. No es un beneficio para mí no más, sino para todos”, dice Pedro Pablo de Putumayo, que tiene sus metas puestas en que bosques como el suyo puedan recibir pagos por servicios ambientales. Con orgullo cuenta que hace dos años vinieron dos estudiantes de la universidad francesa de Rennes 2 a medir cuánto carbono almacena su bosque.

“El daño fue verídico, pero respuesta satisfactoria no hubo. Fue la negación de la queja. Así se quedó”, dice.